What We Learn from Copying

When I was studying literature in college, a professor once assigned us a task: Pick a passage from the book we were reading, and write it down. Copy it by hand, word for word.

I thought, why? What am I going to get out of that?

Well, I should have known better. It was revelatory.

From Nicholson Baker:

Copy out things that you really love… You’ll find that you just soak into that prose, and you’ll find that the comma means something, that it’s there for a reason, and that that adjective is there for a reason, because the copying out, the handwriting, the becoming an apprentice—or in a way, a servant—to that passage in the book makes you see things in it that you wouldn’t see if you just moved your eyes over it, or even if you typed it.

And Hunter S. Thompson:

If you type out somebody's work, you learn a lot about it. Amazingly it's like music. And from typing out parts of Faulkner, Hemingway, Fitzgerald - these were writers that were very big in my life and the lives of the people around me - so yeah, I wanted to learn from the best, I guess.

When I was first learning graphic design, one of my hobbies was something called vexel art. It’s a niche I discovered through DeviantArt that involves creating perfect replicas of photographs in a style that mimics vector art, but using raster tools.

You may think that sounds pointlessly tedious, and unoriginal to boot. You’d be mostly right. Each piece took hours upon hours, and hundreds of individually drawn layers in Photoshop, to create.

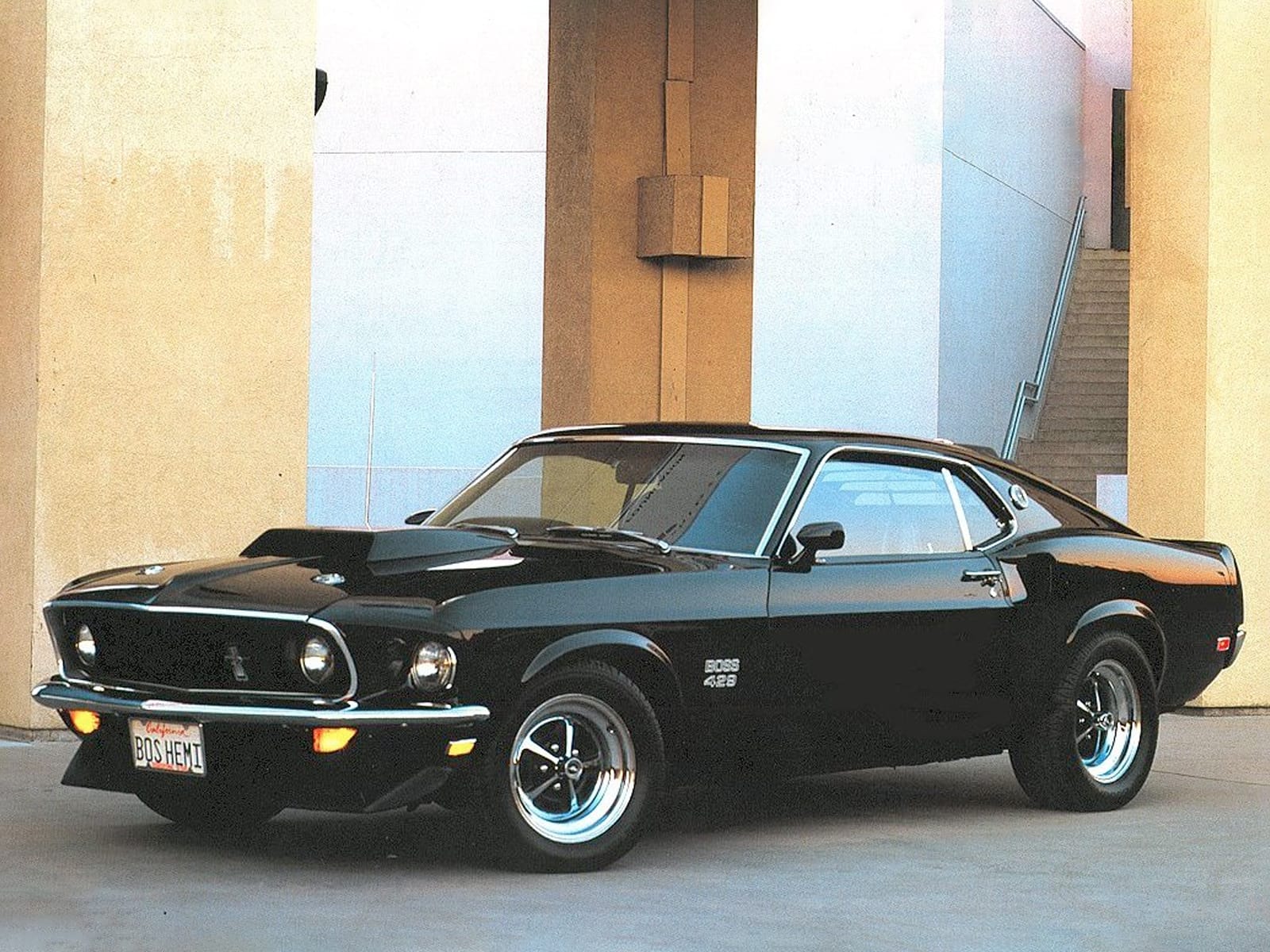

When you’re studying something with your eyes—a written passage, a painting, a Ford Mustang, whatever—your mind jumps to conclusions. It fills in gaps. It’s feature, not a bug, of our brain.

But when you set out to copy that thing, your eye is forced to examine every detail with an equal level of focus. As a result, you become more familiar with the work than you could any other way.

As a product designer, I’ve spent hours fine tuning the optical details of my work – spacing, color, alignment, hierarchy, and so on. When you’re learning to master this skill, it can be difficult to know what makes one design work better than another when the difference lies in the tiny, atomic-level decisions like what shade of light gray to use for borders and whether to space two elements 10px or 12px apart from each other.

If I were teaching a design class today, I’d assign my students the same task my professor assigned me: Find a design you like, and copy it pixel for pixel. The details of the composition that your brain doesn’t see, even though you’re looking at them—the ones that are key to a successful design—will reveal themselves.